A Divided Case

Reading and Writing with Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey

In Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, after a rich general maltreats the heroine by sending her away from the abbey without ceremony or explanation — the titular abbey at which she had just spent a delightful few weeks with his daughter and son (with whom she was in love) — Jane Austen gives a somewhat brief summary of why the general reversed his behavior towards her and acted so strangely (he found out she wasn't rich and that her connections were not as illustrious as he had assumed). Austen then follows that summary with this paragraph:

“I leave it to my reader's sagacity to determine how much of all this it was possible for Henry [the heroine's lover] to communicate at this time to Catherine, how much of it he could have learnt from his father, in what points his own conjectures might assist him, and what portion must remain to be told in a letter from James [the heroine's brother]. I have divided for their case what they must divide for mine. Catherine, at any rate, heard enough to feel that in suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty.”

(Austen, 215)

This is not an easy paragraph. I had to pause and think it over for some minutes, especially the line, “I have divided for their case what they must divide for mine.” The more I thought about it, however, the more I was delighted and immersed by the way Austen breaks the fourth wall and invites the reader into the act of imagination. It is immersive because she invites the reader to use the same sort of imagination that a writer uses when imagining a story. “I have divided for their case what they must divide for mine,” she says. Meaning that we must imagine for ourselves the various conversations and snippets of letters that would allow Catherine to piece together everything that Austen has just related about the General's behavior and character.

This is a bold and creative choice, a choice that I don't think many writers today would consider. Especially in today's age, where so much content is designed to be fast and easy in order to hook us, I feel pressure as a writer to trust as little to the reader's sagacity as possible. Most online writing advice tends towards simplicity and clarity. The number of times I have heard friends and acquaintances remark that they just don't really read anymore seems to be going up, and I wonder: What if I use a word they don't know? What if I am not clear enough? What if it's too weird? What if they wrinkle their eyebrows and scroll away? How many readers did I lose in those first two paragraphs? I wonder, and then wonder if I even should wonder, because as a writer I cannot really control or know my readers (despite the often repeated necessity of “knowing your audience,” I think this phrase really doesn't apply to fiction unless you are writing it with the marketing already in mind), because if I underestimate some readers' sagacity I will offend others by condescending to think too much of my own.

There is an important distinction that must be made here, between writing that trusts the reader and writing that is unclear because it is sloppy. As E.B. White once said, “Be obscure clearly! Be wild of tongue in a way we can understand!” There is a tendency to rely on absurdity to make stories exciting, and I cannot support throwing words and absurd scenes together simply because they are shocking and entertaining. “When you say something, make sure you have said it.” (White, 79). I am not against whipping lazy writers into shape, but the question I would like to ask is, “What about lazy readers?” Because Jane Austen's style is very clear. We cannot accuse her of muddiness. Yet it is not easy to read even when you account for semantic drift and unfamiliar Britishisms. Even for a well-bred man in the nineteenth century, I dare say that her writing requires thought and adjustment and practice and sometimes a dictionary. In short, it requires sagacity.

Popular unwillingness to read “Literature” is not helped by the prestige of “Great Literature,” far from it. In reading a classic, a reader can't help but feel that this book ought to have some important historical or societal point, and they are made to feel stupid for not “getting it.” Or they start a foreword only to find themselves in the midst of a twenty page dissertation that spoils the entire plot. Or they choose a classic that is not to their taste or too depressing and conclude that all classic novels are hard and depressing. There are certainly some that are difficult, and even the ones that are more or less accessible are going to require some adjustment to a different historical period and a different culture. If the reading muscle has atrophied, it is going to be somewhat painful to exercise it, but I think most of us would be surprised by how fast we can acclimate and learn. And by how delightful and thrilling it is to read contemporary sources instead of preprocessed and filtered accounts. And by how much beauty and relief is buried in a well told account of human tragedy. If you want to really immerse yourself in the French revolution, there is no better way than reading Les Miserables. If you want to journey to a fantasy world of beautiful houses and clever love and intrigue among the wealthy, there is no better way than reading Jane Austen. If you want to mine the depths of the human soul and confront your most forbidden and tragic thoughts with love, there is no better way then Crime and Punishment. And if you don't like something, that's okay. Books are not meant to cater to your every whim. If you don't like something, it is a great opportunity to examine why you react the way you do, which can lead to self knowledge and improvement. Aversion is a great opportunity to form your own opinions and exercise your critical muscle, which will help you in many other situations in life.

But what am I doing? I am not really talking to you, am I. I am talking to myself. I am trying to justify my way of reading and writing, and gratifying my pride. The world is loud. I wonder why I listen to it. Well, reading old books needs reinforcement in this age. Jane Austen was right, and she still is:

“We [novel writers] are an injured body. Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species of composition has been so much decried.”

“And what are you reading, Miss — ?”

“Oh! It is only a novel!” Replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference.

”...Only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language.”

(Austen, 32).

I cannot help but feel that Jane Austen would not have been published in 2026, or if she did get published she would not have been very successful. An editor would probably say, “This fourth wall breaking breaks the pace and confuses the reader. You've got to cut that all out, or you've got to make it funny, because that's all fourth wall breaking is good for, like Deadpool. And the heroine. She's not got much going on does she? She should have some fatal flaw, like a drug addiction. Oh and why doesn't anybody have sex? This is supposed to be a romance novel isn't it? The general's not evil enough. He's just sort of rude and it doesn't quite make sense why Catherine would suspect him of murder. He should have sex dreams about her. The plot is too realistic it's boring. If you want to have a plot that's boring and realistic you've got to add more sex and existentialism.”

Perhaps this hyperbolic indulgence of bitterness is not helping my chances with readers or editors, but if I could turn it into something productive, I think it shows how very refreshing it is to read Jane Austen in 2026. The passage of time has made her perspective more illuminating than any insert-hot-new-nonfiction-title-here, and more revolutionary than insert-hot-new-fiction-bestseller-title-here. Reading Jane Austen also shows us that the passage of time has not changed some things. For instance, Catherine has a great deal of anxiety about social misunderstandings. We still do that today. Catherine is also the victim of the belligerent opinions of men who refuse to listen to anyone but themselves. That still happens. Class distinctions were definitely more rigid for her, but I don't think money and fame mean as little to us now as we would like to assume. Those same pressures — how nice your clothes are, what sort of car (or carriage) you drive, how you eat and how you speak and what connections you have — these pressures have not gone away, and are not much less potent because we try to pretend they don't exist. The wealthy still hold a disgusting share of the income. People still don't believe in reading novels. We are still in need of voices like Austen who can hold up the mirror to us without bitterness or distorted filters.

If there is one critique I would give to Austen's tirade about novels, it is that novels are very hard to write, and that few are as successful as her own. This is why readers are necessary, and why writers care so much about them. We are not always the best judge of our work, and neither are readers; but in the exchange of stories and feedback we can shape each other. If we can summon the stamina to approach this relationship with love and humility, then we can shape each other for the better. As Austen says, “Let us not desert one another.”

#essay #non-fiction #JaneAusten

Works Cited

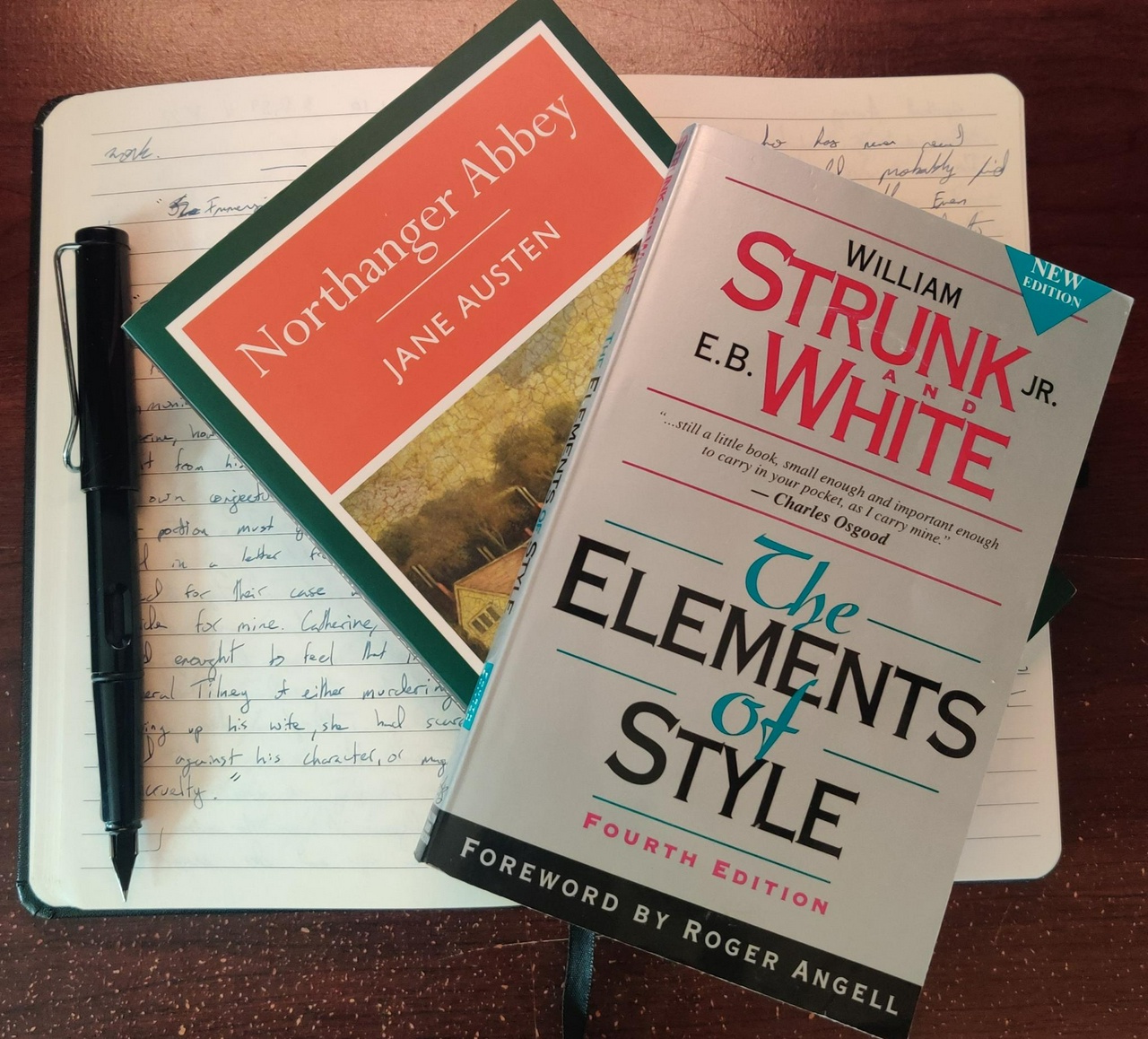

Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey. Aucturus Publishing Limited, 2011, 1817.

Strunk, William Jr. & White, E.B. The Elements of Style. Fourth Edition. Allyn & Bacon, 2000, 1979.

Well, this one came out of nowhere. I read Northanger Abbey and just couldn't help myself. I feel it is somewhat indulgent, but I hope if you made it this far that it was enjoyable and not unedifying.

Thank you very much for reading! I greatly regret that I will most likely never be able to meet you in person and shake your hand, but perhaps we can virtually shake hands via my newsletter, social media, or a cup of coffee sent over the wire. They are poor substitutes, but they can be a real grace in this intractable world.

Send me a kind word or a cup of coffee:

Buy Me a Coffee | Listen to My Music | Listen to My Podcast | Follow Me on Mastodon | Read With Me on Bookwyrm